I’m an avowed skeptic when it comes to the belief that our understanding of ourselves has achieved new heights in modern society and classic texts regularly remind me of this. This also occurs frequently when scientists, through their research, confirm what we term conventional wisdom.

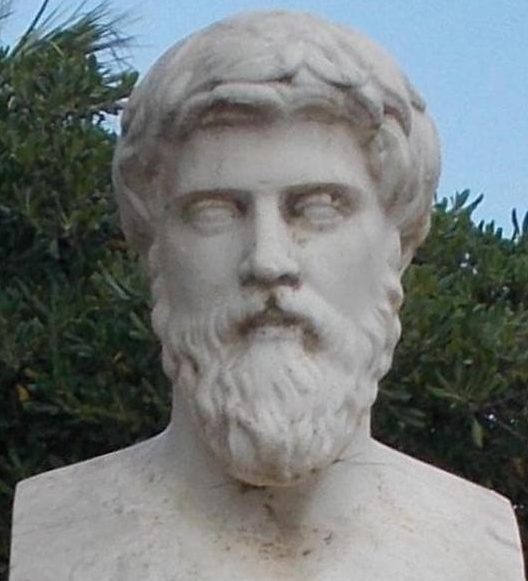

Below is a passage from Plutarch’s Moralia, written circa 100AD, almost 2,000 years ago. It is a part of his essay titled “The Education of Children.”

Now it is a fortunate thing and a token of divine love if ever a heavenly power has bestowed all these qualities on an one man; but if anybody imagines that those not endowed with natural gifts, who yet have the chance to learn and to apply themselves in the right way to the attaining of virtue, cannot repair the want of their nature and advance so far as in them lies, let him know that he is in great, or rather total, error. For indifference ruins a good natural endowment, but instruction amends a poor one; easy things escape the careless, but difficult things are conquered by careful application.

Plutarch, The Education of Children, Moralia I (Loeb Classical Library)

He is addressing a concern that has spawned several popular books in the self-improvement category. The main one, based on the research of Carol Dweck, a Stanford scientist, asserts that one’s success is not necessarily tied to their inborn ability and that with the right mindset – a “growth mindset” – one can achieve anything they apply themselves to.

It took Dweck several years to research her hypothesis after which she published an almost 300-page book, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, to convey what Plutarch did almost 2,000 years ago in one paragraph which, in turn, is summed up conventionally as: you can do anything you set your mind to.